Several weeks ago, a friend told me this story about an interaction between her tween son and her mother. Since many of us are gearing up for big family events tomorrow, this topic is something worth thinking about. My friend, a 30-something-year-old Black mother of two in Texas, had this to say:

So today she apparently asked my 12 yr old if he could help her get 2 gallons of water from her car and he said no. She came to snitch and I’m sure was trying to embarrass him and I just said “I’ll help you.” He seemed annoyed she interrupted our conversation to tell me that. My family has no respect for children. I honestly assumed he didn’t feel like it. He had just gotten home and rode his bike from school today and he was getting his snack together. I wouldn’t want to stop preparing food to get water either when it can wait. It wasn’t perishable food she was asking for help with but it honestly didn’t matter to me. I teach them ‘you can always ask but sometimes the answer is no.’

She explained further that there is some background between her son and her mother. It seems she oversteps her bounds and tries to impose her ideology on the children. My friend’s son receives her actions as judgmental. When she asked “Do you want to help me with something?” he answered literally “No” because he was busy.

I can almost see the pearl-clutching! I come from a very Southern, very authoritarian background where adults owned all rights to the labor of children and children had no right to refuse. It was considered the height of rudeness and deserving of quite a spanking. I’ll grant that a young boy who had the strength to ride his bike all the way home from school surely has the strength to go outside to grab a couple gallons of water. Plus, it’s perceived as rude not to be considerate of an elderly relative’s wishes.

Before we had our children, Peaceful Dad and I created family guidelines, and one of those guidelines is “We always choose to help.” We teach our children that we are the heart and hands of Christ to our world. We help out of love. Not obligation. And never because someone wants to assert a flawed belief that my children should be subordinate. I don’t entertain discussing my kids negatively like this grandmother did, no matter who the adult is. I will always ask the adult to speak directly to my child if there’s been a problem. I can be there for moral support, but my child needs to be part of the conversation.

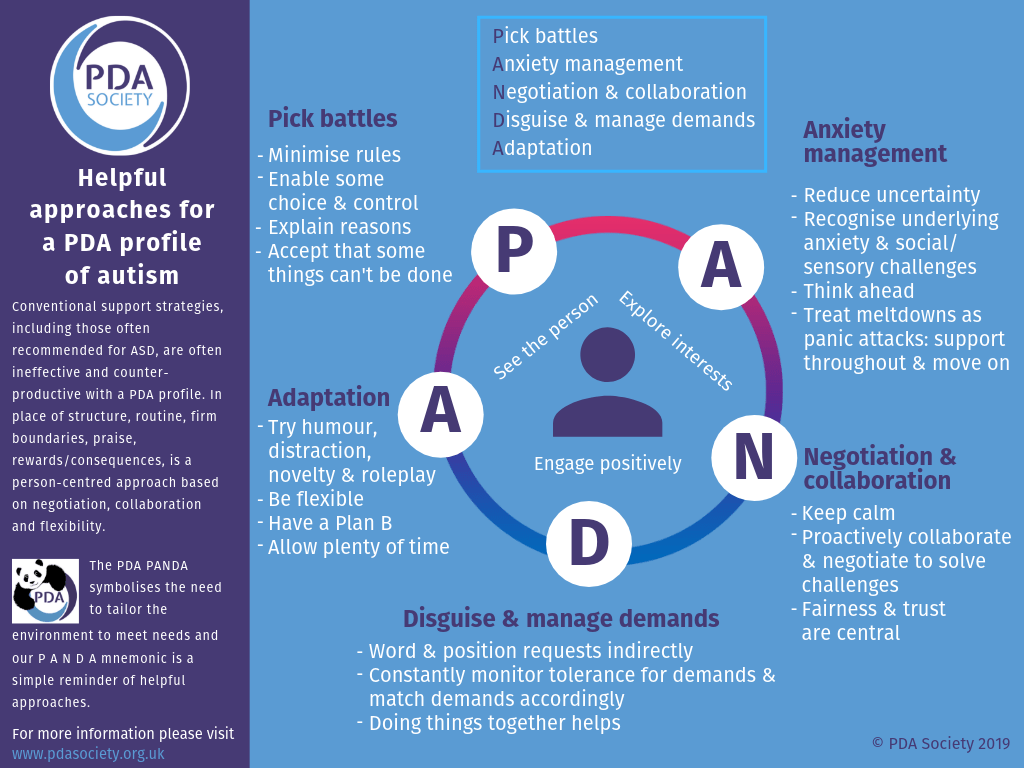

Had this scenario happened in my house, I probably would have broached the topic with my son to understand his perspective while affirming that no one is obligated to help anyone. I would want my son to know that there are relationship consequences for refusing a request for help, particularly since there exists a social expectation that children are to serve adults. This is something children need to be aware of, and it’s something worth discussing as we guide our children through the trials of childism.

Her entitlement was completely inappropriate. No one has a right to anyone else’s labor. I imagine my friend’s son would have graciously agreed had his grandmother asked, “When you finish eating your snack, would mind helping me get some gallons of water out of my car?” So, let’s flip this around. Is it not also rude of an adult, knowing this child was tired and hungry, to demand assistance with a non-urgent matter while the child is in the middle of making himself something to help him recover from his long day and his long ride? Could the request not have been made in a more understanding and compassionate way wherein both of their needs could have been met?

The trouble here is that, for many adults, the outcome isn’t as important as the interaction. They say they like seeing kind, cooperative, and respectful children, but what they really expect is deference and obedience.

That’s childism!

Rudeness is a matter of perception. In this case, the requester ultimately got the help she was requesting, so the problem was solved. I don’t want to suggest that kids be encouraged to break social “rules” for the sake of being controversial. I think it’s important for children to be aware of expectations and cultural consequences. But, at the same time, we also need to be holding adults accountable for how they interact with kids, and we need to instill self-confidence and self-worth in our kids so that they know how to navigate social expectations with grace and wisdom.

If a child is uncomfortable with a request being made of them, we can be there to help guide the conversation. Otherwise, we can give kids room to work out their own relationships and support them in upholding boundaries… even with elderly relatives. And, even at big family events.

I asked my friend what had changed since her own childhood that caused her to support her son in his interaction with her mother. She said:

In the past I would have felt pressured into forcing him to do something he didn’t want to do. When my daughter came along I realized that I was raising my kids differently than I was raised and than the kids in my family were being raised. One day my grandma asked my 1 year old for a hug at easter and my nephew who was about 4 said she “don’t do hugs.” My granny said “I don’t care, come give me a hug girl!” It was right then that I was like “oh hell no!” She is not about to force herself onto my child and traumatize her and then leave me with the job of cleaning up. So I stopped her in that moment and said “we don’t force physical contact on people,” and I looked at my daughter and said “can you wave bye bye to granny?” And she didn’t do that either and I said “maybe next time” and shrugged it off. That’s when I started looking into ways to fend off my pushy relatives because I knew there would be more situations like these in the future.

I went from spanking my son to not believing it was necessary I hardly ever took my kids out during nap time or would leave when they got tired because they just slept better at home and to prevent putting them in situations where they were over tired and would act out. Long ago, I decided that just because something is the way we’ve always done it, that doesn’t mean it’s not wrong.

Just because something is the way we’ve always done it, that doesn’t mean it’s not wrong. That is an entire lesson right there on its own! We can teach our children how to say, “I’m busy right now, but I’ll be with you as soon as I finish.” We can foster relationships in our children’s lives that meet their needs and those of the adults they care about. When the challenge in a child’s life is a social expectation, let’s allow genuineness and honesty to win out. It’s ok for children to say “not now” or even “no” to adults. Unclutch those pearls!

So, how do you instill a sense of selflessness in your kids? How do you foster the development of a human who enjoys being helpful whenever possible? I’m sure there are many ways families are doing this every day (and I’d love to hear from you in the comments!) I’ll mention one of the ways that has been invaluable for my family. We include our children in our everyday lives. Sounds pretty simple, but it takes planning and patience. It can be difficult to allow kids to help in their own developmentally appropriate ways. It’s messy and time consuming, but it is wonderfully affirming for your child! If you’d like to try it out, the key is to resist the urge to do things for your children. Don’t take over. If you want to insert yourself into the activity, help out! Demonstrate by modeling what’s expected. Openly speak with your child about the expected outcome, step by step. Children don’t know the process to get to an end result until they learn it. For example, including children in putting laundry away might look something like this:

- Parent invites the child to help

- Child accepts

- Parent quickly explains what’s about to happen – “We’re going to take the clothes out of this laundry basket, fold them neatly, put them back into the basket, and then put them into their drawers. I’ll help you!”

- Parent demonstrates how to fold an item of clothing and hands some clothes to the child

- Parent and child go through the steps together

Many children will likely not be able to fold to an adult’s expectation, be able to open drawers and sort, and the like. Some direction is helpful, but allowing the child to try and accepting their effort as is goes a long way to instilling a love of helping in a child. And, start young. Thank your infant for helping you pick up toys even if it becomes a game. There are so many ways to include and appreciate kids. You and your child will figure it out together.