Almost all children will go through periods where they lash out in some way and spitting, hitting, biting, and kicking seem to be the most common behaviors. What should you do when your child lets loose? It’s critical to understand what underlies the behavior. We could fancy ourselves investigators for this purpose. What precipitated the event? Here’s a list of replies your child might give you if they could.

- I just felt like it.

- I need your attention.

- I need freedom. Give me space.

- I’m tired.

- I’m hungry.

- It’s too noisy in here.

- My sibling took my toy.

- Stop touching me!

- You’re not listening to me.

- This is fun!

- I’m frustrated.

- Let me do it my way.

- I saw my sibling doing this and I wanted to try.

- I was curious what would happen.

- I’m anxious.

- My body doesn’t feel good.

Addressing Needs

Both my 2 year old and my 4 year old spit, hit, bite, and kick at one time or another, so I completely understand the frustration and that gut feeling of wanting to react in an unkind way. But stop! Stop for a minute and think about what’s happening. Let’s categorize the “whys” for greater understanding.

Attention

I need your attention.

You’re not listening to me.

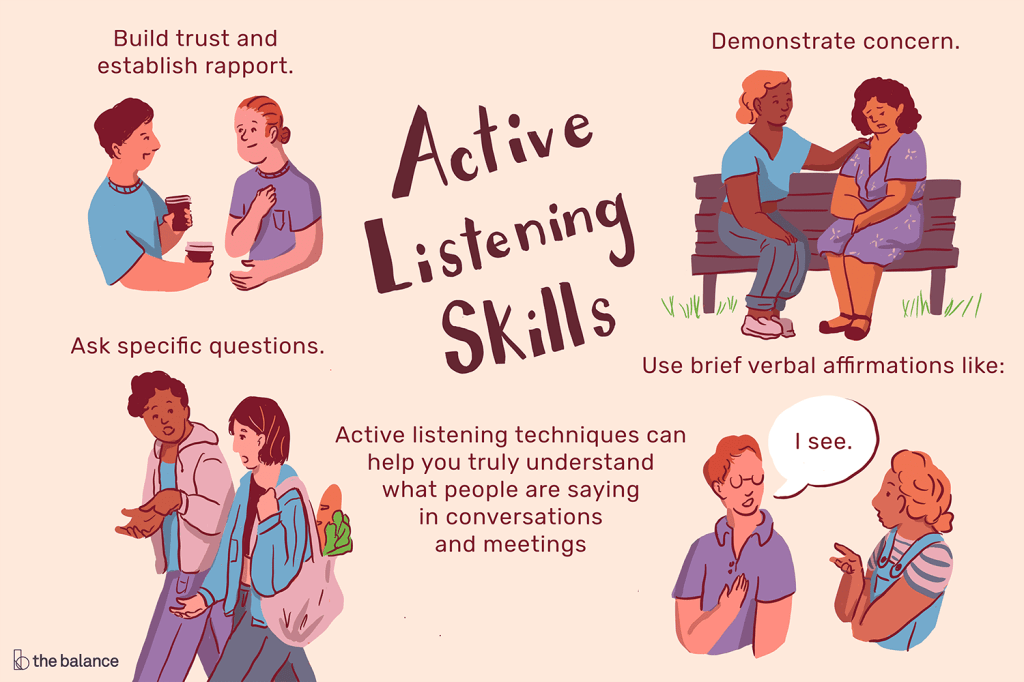

Sadly, we’ve been conditioned to see children as annoyances who drain our time and our energy. We don’t want to “give in” when our kids express their need for our attention in undesirable ways. However, empathetic communication actually increases well-being. It’s not simply a way to meet our children’s needs. It also improves our relationship. If your child needs your attention, try a little active listening.

Some of the pitfalls I face when it comes to listening to my kids include thinking of something else while my child is communicating, trying to figure out what I’m going to say next, and attempting to manipulate the direction of the conversation. If you’re anything like me, one or more of those statements might resonate.

Professional communicator and educator, Julian Treasure, recommends a four-step approach to listen with investment:

- Receive: Absorb what the child is telling you

- Appreciate: Pause and think

- Summarize: Paraphrase what you’ve understood

- Ask: Learn more

If you know your child needs your attention, give it freely. Silence those harmful voices telling you not to spoil your child. You cannot spoil a child with love and affection. Quite the contrary, kids who are perceived as spoiled tend to be those children who have a) not had their boundaries respected so they react with belligerence or b) not been given enough attention and therefore do not trust that their needs will be met.

Boundaries

I need freedom. Give me space.

My sibling took my toy.

Stop touching me!

Let me do it my way.

In our childist culture, it’s easy to get caught up in “what’s mine is mine and what’s yours is mine” thinking when it comes to children. We’ve got to work toward flipping that perspective around and radically respecting our children’s autonomy.

Years ago, sexuality educator, Deanne Carson, made headlines when she advocated for asking infants if it was ok to give them a diaper change. She acknowledged that they wouldn’t be able to consent, but said that asking for consent and pausing to acknowledge them lets children know that their response matters.

I fully admit that I scoffed at her comments at the time, even though I was already three years into my Peaceful Parenting journey, as I was sorely lacking an understanding of childism.

Yes, you can let your baby know you’re about to change their diaper. Consent does start from birth and it never ends. We must prioritize navigating our children’s demands for bodily autonomy and their health-related needs. It’s not easy or simple, but it’s our responsibility.

If you know your child is enforcing a boundary, respect it. Bottom line. For guidance on helping siblings through the tough task of sharing/turn-taking, check out this article.

Discomfort

I’m tired.

I’m hungry.

It’s too noisy in here.

I’m anxious.

My body doesn’t feel good.

I’m frustrated.

Discomfort shows up physically and mentally. Both are completely real and valid. In our culture, we tend to tell children how they’re feeling. We dismiss skinned knees with “You’re ok” and toileting urgency with “You just went!” Children are too often forced into the constraints of our schedules and whims, and it’s not ok. Kids deserve for their needs to be met. Where the dominant culture tells us that our children are manipulatinrg us, it is incumbent upon us as Peaceful Parents to reject that perspective wholesale. If our children need to use the bathroom, they will. If they feel sick, we listen. If they are anxious, we soothe.

And, a note to those who fear all this responsiveness will lead to spoiling children. It won’t, but as we get into more complex needs, our responses may need to evolve. All children need accomodations, some more than others. Autistic Mama wrote a fantastic piece called Are You Accommodating or Coddling Your Autistic Child and really it applies to all children. In it, she explains:

The line between accommodating and coddling boils down to one specific question.

What is the Goal?

You have to ask yourself, what is the goal here?Let me give you an example…

Let’s say your child has a history assignment and is supposed to write two paragraphs on the civil war.

What is the goal of this assignment?

To prove knowledge of history.

Now any tool or strategy that doesn’t take away from that goal is an accommodation, not coddling.

So typing instead of writing? Accommodation.

Verbally sharing knowledge of the civil war? Accommodation.

Writing a list of civil war facts instead of using paragraphs? Accommodation.

Because the goal of the assignment is a knowledge of history, not the way it’s shared.

We can empower our children to solve their own problems by showing them how to be problem-solvers from a young age. We can teach our children to ask for what they need and demonstrate that their needs matter by obliging their requests. As they get older, we can empower them to seek reasonable accommodations in a variety of environments by considering what needs they must have met in order to succeed and to advocate for themselves.

I would be remiss not to mention one thing here of great importance to the Autistic community. AUTISTIC PEOPLE ARE NOT INHERENTLY VIOLENT. Violence is not a criteria for diagnosis. So many people ponder why it seems like Autistic children tend toward aggression. Well, imagine having to endure all the little things you dislike (flavors, sounds, textures, etc.) all the time and then being treated as though you’re a burden for asking for it to stop. You might be driven to aggression as well. It’s hard being Autistic in a world that isn’t made for you. Meet the needs of Autistic kids and you’ll see a drastic decline in any aggression.

If you know your child is uncomfortable, try to help relieve that discomfort. Some children are unable to clear saliva and may spit or drool as a result. This is common with children who need lip or tongue tie revisions. If your child is anxious, try these measures. Whatever is going wrong, seek out a solution to support your child rather than punishing them.

Play

This is fun!

I saw my sibling doing this and I wanted to try.

I was curious what would happen.

I just felt like it.

Our children’s top job is to learn through play. We must leave some room for childlikeness, even when it comes to things that are as upsetting as aggression. As strange as it might seem to us, children do many things because they’re testing out how their bodies move and what effect they can have on their environment.

If you know your child is playing, try directing their play into a form that is more conducive to your family’s lifestyle. Getting down on the ground to wriggle around kicking can be fun. Just make sure the goal truly is play or your actions could come across as mocking.

Tips for Interrupting Aggression

- Respond Gently. First and foremost, try not to meet force with force. Understand that children start out several steps ahead of us in terms of emoting because of their stage of brain development. The calmer we are, the better we can respond. And, if you need to physically stop your child from harming you, use the least force you possibly can.

- State Your Boundary. Let your child know your expectation in clear, unambiguous terms. Try “I know you want to hit me because you’re angry. I can’t let you” or “I won’t let you hurt me.”

- Engage the Three Rs. When you need to engage with a dysregulated child, remember to Regulate, Relate, and Reason. For many children, just acknowledging and empathizing alone will resolve the aggression, so that you can work toward meeting the need.

- Give Your Child an Alternative. Understand that there are two types of aggression: the type you can mediate, like hitting and the type you can’t, like spitting. You can stop a child from hitting, biting, and throwing. You can’t stop a child from spitting, peeing, or pooping. In all cases, it’s crucial to address the underlying need, but you may also be able to introduce an alternative such as giving a child a chewie to chomp in place of spitting or even a towel to spit into. Whatever alternative you choose must be desirable to your child and easy to access when the need calls.

- Resolve the Underlying Need. I cannot stress enough how important this one is. You’ve got to figure out what’s going wrong for your child and help them fix the problem. For example, when a child is pushing his sister down over and over again, take notice of why it’s happening. Is the sibling standing too close? Bothering the child while he’s playing? Once you figure out the need, the solution is often simple enough. Help the kids regulate and then invite the other child to help you in the other room.

- Give Children the Words. Kids do not instinctively know how to ask for what they need. I hear a lot of parents telling children to “Use your words.” Let me tell you how very unhelpful that is! Parents, please use YOUR words. Give your child the language they should use to have their needs met, even if you have to do it over and over and even if you have to ask questions to get there. The more you model how to use language under stress, the more capable your children will be in following suit.

- Avoid Confusing Messaging. While you’re giving your child the words, remember that children think in very concrete terms. There’s a series of books by Elizabeth Verdick called the Best Behavior Series and it includes such titles as Teeth Are Not for Biting, Feet Are Not For Kicking, and Voices are Not For Yelling. Read those titles again… carefully. How do we chew our food without biting? How do we swim without kicking? And how to we call out for help without yelling? It’s not logical, so it’s not going to make a lot of sense to a child. Kids might learn in spite of these messages, but it’s best to avoid them if possible.

- Consider an Assessment. If your child’s aggression doesn’t seem to be manageable using any of the tips above, consider that something deeper may be going on and that you might not have all the information you need to meet their needs. Put aside concerns about stigma and work with a professional to help you and your child understand what’s happening.